How To Become More Self-Sufficient Without Starting a Full-Blown Farm…

Want to start preserving your harvest, making your own soap, or building a backyard root cellar — but not sure where to begin? “Homesteading Advice” gives you instant lifetime access to 35+ practical homesteading books on food preservation, veggie gardening, DIY natural cleaning products (save over $250 per year with this skill alone), brewing, off-grid energy, and a whole lot more…

Click Here To Check It Out Now!

School gardens are blossoming across the country. Over the past decade, school gardens have grown from a rarity to a well-known concept that continues to gain traction in schools small and large, public and private, rural and urban.

Their proliferation makes perfect sense as soon as you start to investigate the benefits of gardening with students. First and foremost, school gardens teach students how to grow and harvest their own food – which is perhaps one of the most vital skills a person can possess. Additionally, research shows working in school gardens can:

- Increase students’ science achievement scores

- Improve social skills by cultivating empathy and teamwork

- Increase students’ knowledge of nutrition and their willingness to consume fresh produce

- Improve emotional literacy

- Develop a sense of community and responsibility

- Instill lifelong appreciation for the natural world.

In providing hands-on learning opportunities, school gardens also cater to students with diverse learning styles. As a result, they’ve been shown to engage and focus students who may otherwise exhibit disciplinary issues in the classroom. Gardens can also beautify a school’s campus and instill a sense of school pride in students, teachers, and administrators.

These benefits should encourage anyone – teacher, administrator, parent, or student – to advocate for designing a school garden at their own school. Not sure where to start? Here’s a basic guide to grow your school garden dream into a reality.

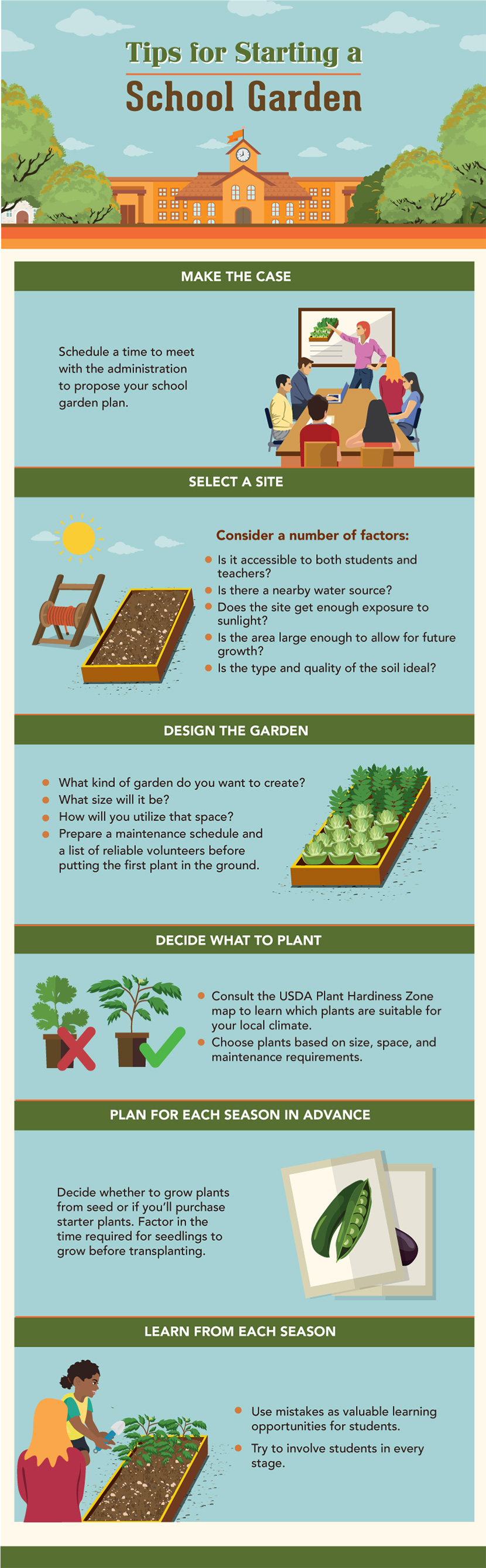

Tips for Starting a School Garden

Ready to embrace gardening at your school? Follow these steps for a healthy harvest.

Make the case

Before designing a school garden, you’ll likely need approval from critical parties (namely school administrators and possibly funders). Unless the administration is already on board, prepare a justification for why the school should invest in a garden.

Schedule a time to meet with the relevant parties and prepare a presentation in advance that outlines the benefits of school gardens to the students, school, and community, and details goals for the program. Prior to meeting, consider recruiting parents, staff, teachers, and/or community members who are willing to donate their time and expertise, which demonstrates that the community is willing to help out. This can make gardens seem much more manageable to skeptical administrators. If administrators are worried about funding, consider applying for grants, soliciting supply donations, or pursuing other creative ways to fund school garden projects.

Select a site

Once you have approval, it’s time to get serious about garden design. Start by choosing where the garden(s) will be located. Consider a number of factors, including whether the site is accessible to both students and teachers, has a nearby water source, gets enough exposure to sunlight (aim for a minimum of six hours of sun exposure each day), is large enough to allow for future growth, and has soil that is of good quality for growing flowers and vegetables.

Design the garden

Before planting anything, it’s important to think about what kind of garden you want to create, what size it will be, and how you will utilize that space.

Start by deciding on a garden type: Will you plant directly in the soil, build raised beds, or plant in straw bales or containers? The site you select will help determine your options. Speaking with students, teachers, and administrators should give you a good sense of which type of garden best suits everyone’s needs. If you feel a bit lost, it may be worthwhile to consult a professional.

Once you’ve settled on a garden type, it’s advisable to draw up some garden designs.Ideally, you’ll want to solicit feedback from as many relevant groups as possible (think students, teachers, and administrators) in order to make sure that the design suits various needs. The sketch should include the dimensions as well as where the site is relative to water, equipment, compost, and so on. You’ll find yourself referring to this repeatedly as you decide what and where to plant.

While you’re at it, start thinking about how you will tackle soil preparation, garden maintenance (such as weeding and watering), waste reduction (such as composting), and so on. Prepare a maintenance schedule and a list of reliable volunteers before putting the first plant in the ground.

Decide what to plant

In order to know what to plant, you need to understand of your region’s growing zone. Start by consulting the USDA Plant Hardiness Zone map to learn which plants are suitable for your local climate. Also take into account the size, space requirements, and maintenance required to grow each plant. And don’t forget to consider the season in which you start the garden; certain plants grow best at certain times of the year.

Once you create a list of location-appropriate plants, enlist students’ feedback to learn what they’re most excited to grow. You may also consider choosing plants based on a theme that connects to lessons taught in the classroom.

Above all else, remember to start small when planning the first planting: You don’t want to overwhelm students or volunteers with a huge harvest or challenging maintenance needs.

Plan for each season in advance

No matter which plants you decide to grow, it’s wise to plan for each season well in advance of planting time. For example, it’s advisable to start planning your spring garden in January. After putting together a plan for the season’s plantings, decide whether to grow plants from seed or purchase starter plants. If growing from seed, remember that some plants need to be started indoors several weeks (and maybe even months) before they’re ready to be transplanted into an outdoor garden.

If you’re operating on a small budget, it’s also helpful to think about potential budget-friendly resources. Can you send a letter home with students asking their parents to donate extra gardening tools and gloves? Could local farmers or local garden clubs donate seed packets or volunteer their expertise? Could local college students volunteer their time? There are all kinds of resources out there – the sooner you investigate these options, the better chance you can stay on budget.

Prep the soil

If you’re planting directly in existing soil, you need to prepare it for planting. This is assuming you already tested the soil and deemed it fit for gardening. If the soil hasn’t been planted in a long time – or ever – it’s probably best to till it; you can do so manually or with rented or borrowed equipment. Just be careful not to over-till, which can compact the soil. (A good rule of thumb is to only till each row one time.) Be sure to till close to the day you plant so the soil is still broken up by the time you add plants. If you built new raised beds or container gardens, then add fresh soil before planting.

Learn from each season

After all the planning is done, there’s nothing left to do but get down in the dirt and plant, weed, and tend to your garden. You may make mistakes along the way, and that’s okay – use them as valuable learning opportunities for students. Try to involve students in every stage, from designing the garden and preparing the soil to planting the first seeds (or starter plants) and harvesting the fruits of their labor. Involvement helps instill a sense of pride, responsibility, confidence, and investment. The more students, teachers, and volunteers work in the garden, the more everybody can learn how to tend it so it stays healthy and produces food for years to come.

While planning and caring for a school garden takes a lot of work, it’s also a lot of fun – and getting students engaged makes it all the more enjoyable. By approaching school gardening with an open mind and a spirit of natural wonder, you’ll model a great attitude for students and ensure gardening remains rewarding no matter what you harvest. Happy planting! (Via Fix)

If you like this idea, be sure to share it with your friends and inspire someone you know. Anything becomes possible with just a little inspiration…